An ellipse obtained as the intersection of a cone with a plane.

In mathematics, an ellipse (Greek ἔλλειψις (elleipsis), a 'falling short') is the finite or bounded case of a conic section, the geometric shape that results from cutting a circular conical or cylindrical surface with an oblique plane (the other two cases being the parabola and the hyperbola). It is also the locus of all points of the plane whose distances to two fixed points add to the same constant.

Ellipses also arise as images of a circle or a sphere under parallel projection, and some cases of perspective projection. An ellipse is also the closed and bounded case of an implicit curve of degree 2, and of a rational curve of degree 2. It is also the simplest Lissajous figure, formed when the horizontal and vertical motions are sinusoids with the same frequency.

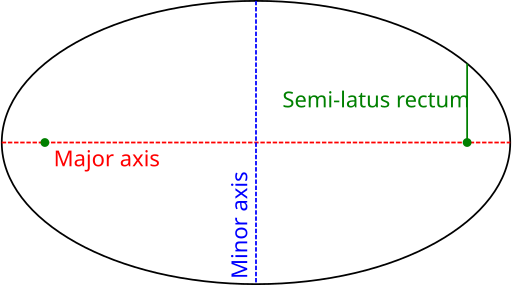

Elements of an ellipse

The ellipse and some of its mathematical properties.

An ellipse is a smooth closed curve which is symmetric about its center. The distance between antipodal points on the ellipse, or pairs of points whose midpoint is at the center of the ellipse, is maximum and minimum along two perpendicular directions, the major axis or transverse diameter, and the minor axis or conjugate diameter[1]. The semimajor axis or major radius (denoted by in the figure) and the semiminor axis or minor radius (denoted by in the figure) are one half of the major and minor diameters, respectively.

There are two special points on the ellipse's major axis, on either side of the center, such that the sum of the distances from any point of the ellipse to those two points is constant and equal to the major diameter . Each of these two points is called a focus of the ellipse.

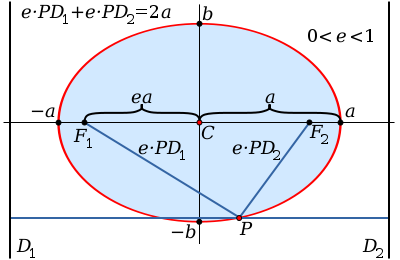

The eccentricity of an ellipse, usually denoted by or , is the ratio of the distance between the foci to the length of the major axis. The eccentricity is necessarily between 0 and 1; it is zero if and only if , in which case the ellipse is a circle. The distance from a focal point to the centre is called the linear eccentricity of the ellipse.

Drawing ellipses

The pins-and-string method

Two pins, a loop and a pen method

An ellipse can be drawn using two pins, a length of string, and a pencil:

- Push the pins into the paper at two points, which will become the ellipse's foci. Tie the string into a loose loop around the two pins. Pull the loop taut with the pencil's tip, so as to form a triangle. Move the pencil around, while keeping the string taut, and its tip will trace out an ellipse.

To draw an ellipse inscribed within a specified rectangle, tangent to its four sides at their midpoints, one must first determine the positon of the foci and the length of the loop:

- Let be the corners of the rectangle, in clockwise order, with being one of the long sides. Draw a circle centered on , having radius the short side . From corner draw a tangent to the circle. The length of this tangent is the distance between the foci. Draw two perpendicular lines through the center of the rectangle and parallel to its sides; these will be the major and minor axes of the ellipse. Place the foci on the major axis, symmetrically, at distance from the center.

- To adjust the length of the string loop, insert a pin at one focus, and another pin at the opposite end of the major diameter. Loop the string around the two pins and tie it taut.

Other methods

An ellipse can also be drawn using a ruler, a set square, and a pencil:

- Draw two perpendicular lines on the paper; these will be the major and minor axes of the ellipse. Mark three points on the ruler. With one hand, move the ruler onto the paper, turning and sliding it so as to keep point always on line , and on line . With the other hand, keep the pencil's tip on the paper, following point of the ruler. The tip will trace out an ellipse.

This method can be implemented with a router to cut ellipses from board material[2] The ellipsograph is a mechanical device that implements this principle. The ruler is replaced by a rod with a pencil holder (point ) at one end, and two adjustable side pins (points ) that slide into two perpendicular slots cut into a a metal plate.

Ellipses in physics

Elliptical reflectors

If the water surface is disturbed at at one focus of an elliptical tank, the circular waves created by that disturbance, after being reflected by the walls, will converge simultaneously to a single point — the second focus. This is a consequence of the total travel length being the same along any wall-bouncing path between the two foci.

Similarly, if a light source is placed at one focus of an elliptic mirror, all light rays on the plane of the ellipse are reflected to the second focus. Since no other smooth curve has such a property, it can be used as an alternative definition of an ellipse. (In the special case of a circle with a source at its center all light would be reflected back to the center.) If the ellipse is rotated along its major axis to produce an ellipsoidal mirror (specifically, a prolate spheroid, or prolatum), this property will hold for all rays out of the source. Alternatively, a cylindrical mirror with elliptical cross-section can be used to focus light from a linear fluorescent lamp along a line of the paper; such mirrors are used in some document scanners.

Sound waves are reflected in a similar way, so in a large elliptical room a person standing at one focus can hear a person standing at the other focus remarkably well. The effect is even more evident under a vaulted roof shaped as a section of a prolate spheroid. Such a room is called a whisper chamber. The same effect can be demonstraed with two reflectors shaped like the end caps of such a spheroid, placed facing each other at the proper distance. Examples are the National Statuary Hall at the U.S. Capitol (where John Quincy Adams is said to have used this property for eavesdropping on political matters), at an exhibit on sound at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, in front of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Foellinger Auditorium, and also at a side chamber of the Palace of Charles V, in the Alhambra.

Planet orbits

In the 17th century, Johannes Kepler explained that the orbits along which the planets travel around the Sun are ellipses in his first law of planetary motion. Later, Isaac Newton explained this as a corollary of his law of universal gravitation.

More generally, in the gravitational two-body problem, if the two bodies are bound to each other (i.e., the total energy is negative), their orbits are similar ellipses with the common barycenter being one of the foci of each ellipse. The other focus of either ellipse has no known physical significance. Interestingly, the orbit of either body in the reference frame of the other is also an ellipse, with the other body at one focus.

Keplerian elliptical orbits are the result of any radially-directed attraction force whose strength is inversely proportional to distance. Thus, in principle, the motion of two oppositely-charged particles in empty space would also be an ellipse. (However, this conclusion ignores losses due to electromagnetic radiation and quantum effects which become significant when the particles are moving at high speed.)

Harmonic oscillators

The general solution for a harmonic oscillator in two or more dimensions is also an ellipse. Such is the case, for instance, of a long pendulum that is free to move in two dimensions, or of a mass attached to a fixed point by a perfectly elastic spring.

Phase visualization

In electronics, the relative phase of two sinusoidal signals can be compared by feeding them to the vertical and horizontal inputs of an oscilloscope. If the display is an ellipse, rather than a straight line, the two signals are out of phase.

Elliptical gears

Two gears with the same elliptical outline, each pivoting around one focus and positioned at the proper angle, will turn smoothly while maintaining contact at all times. Alternatively, they can be connected by a link chain or timing belt. Such elliptical gears may be used in mechanical equipment to vary the torque or angular speed during each turn of the driving axle.

Optics

In a material that is optically anisotropic (birefringent), the refractive index depends on the direction of the light. The dependency can be described by an index ellipsoid. (If the material is optically isotropic, this ellipsoid is a sphere.)

Mathematical definitions and properties

In Euclidean geometry

Definition

In Euclidean geometry, an ellipse is usually defined as the bounded case of a conic section, or as the locus of the points such that the distances to two fixed points is constant.

Angular eccentricity

The angular eccentricity is the angle whose sine is the eccentricity, or ; that is,

The distance from the center to either focus is .

Directrix

Each focus of the ellipse is associated to a line perpendicular to the major axis (the directrix) such that the distance from any point on the ellipse to is a constant fraction of its distance from . The ratio between the two distances is the eccentricity of the ellipse; so the distance from the center to the directrix is , or .

When the major and minor semidiameters and are equal, the foci coincide with the center, and the ellipse becomes a circle with radius .

Ellipse as hypotrochoid

The ellipse is a special case of the hypotrochoid when .

An ellipse (in red) as a special case of the hypotrochoid with

Area

The area enclosed by an ellipse is , where (as before) are 1/2 of the ellipse's major and minor axes respectively.

Circumference

The circumference of an ellipse is , where the function is the complete elliptic integral of the second kind. The exact infinite series is:

where (e.g.)

is a binomial coefficient,

A good approximation is Ramanujan's:

or better approximation:

For the special case where the minor axis is half the major axis, we can use:

or the better approximation

More generally, the arc length of a portion of the circumference, as a function of the angle subtended, is given by an incomplete elliptic integral. The inverse function, the angle subtended as a function of the arc length, is given by the elliptic functions.

In projective geometry

In projective geometry, an ellipse can be defined as the set of all points of intersection between corresponding lines of two pencils of lines which are related by a projective map. By projective duality, an ellipse can be defined also as the envelope of all lines that connect corresponding points of two lines which are related by a projective map.

This definition also generates hyperbolas and parabolas. However, in projective geometry every conic section is equivalent to an ellipse. A parabola is an ellipse that is tangent to the line at infinity Ω, and the hyperbola is an ellipse that crosses Ω.

An ellipse is also the the result of projecting a circle, sphere, or ellipse in three dimensions onto a plane, by parallel lines. It is also the result of conical (perspective) projection any of those geometric objects from a point O onto a plane P, provided that the plane Q that goes through through O and is parallel to P does not cut the object. The image of an ellipse by any affine map is an ellipse, and so is the image of an ellipse by any projective map M such that the line M-1(Ω) does not touch or cross the ellipse.

In analytic geometry

General ellipse

In analytic geometry, the ellipse is defined as the set of points of the Cartesian plane that satisfy the implicit equation

provided that F is not zero and is positive; or of the form

with

Canonical form

By a proper choice of coordinate system, the ellipse can be described by the canonical implicit equation

Here are the point coordinates in the canonical system, whose origin is the center

of the ellipse, whose -axis is the unit vector

parallel to the major axis, and whose -axis is the perpendicular vector

That is, and .

In this system, the center is the origin

- and the foci are and .

Any ellipse can be obtained by rotation and translation of a canonical ellipse with the proper semi-diameters. Moreover, any canonical ellipse can be obtained by scaling the unit circle of redefined by the equation

by factors a and b along the two axes.

For an ellipse in canonical form, we have

The distances from a point on the ellipse to the left and right foci are

- and , respectively.

In trigonometry

General parametric form

An ellipse in general position can be expressed parametrically as the path of a point , where

Here is the center of the ellipse, and is the angle between the -axis and the major axis of the ellipse.

Canonical form

For an ellipse in canonical position (center at origin, major axis along the X-axis), the equation simplifies to

This is not the equation of the ellipse in polar form, since the parameter t is not the angle of with the X-axis.

Polar form relative to focus

With one focus at the origin, the ellipse's polar equation is

where angle is the true anomaly of the point and the numerator a' is the radius of curvature at the major axis (smaller than b), equaling the ellipse’s semi-latus rectum, usually denoted in such reference as , and also equaling the distance from a focus of the ellipse to the ellipse itself, measured along a line perpendicular to the major axis:

Likewise, the radius of curvature at the minor axis (larger than a) can be similarly denoted as b' or c:

Gauss-mapped form

The Gauss-mapped equation of the ellipse gives the coordinates of the point on the ellipse where the normal makes an angle with the X-axis:

Degrees of freedom

An ellipse in the plane has five degrees of freedom, the same as as a general conic section. Said another way, the set of all ellipses in the plane, with any natural metric (such as the Hausdorff distance) is a five-dimensional manifold. These degrees can be identified with the coefficients of the implicit equation. In comparison, circles have only three degrees of freedom, while parabolas have four.

See also

- Apollonius of Perga, the classical authority

- Ellipsoid, a higher dimensional analog of an ellipse

- Spheroid, the ellipsoids obtained by rotating an ellipse about its major or minor axis.

- Superellipse, a generalization of an ellipse that can look more rectangular or more "pointy"

- Hyperbola

- Parabola

- Oval

- True, eccentric, and mean anomaly

- Matrix representation of conic sections

- Kepler's Laws of Planetary Motion

- Ellipse/Proofs

- Elliptic coordinates, an orthogonal coordinate system based on families of ellipses and hyperbolae

References

- ↑ last = Haswell | first = Charles Haynes | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=Uk4wAAAAMAAJ&pg=RA1-PA381&zoom=3&hl=en&sig=3QTM7ZfZARnGnPoqQSDMbx8JeHg | title = Mechanics' and Engineers' Pocket-book of Tables, Rules, and Formulas | publisher = Harper & Brothers | date = 1920 | accessdate = 2007-04-09

- ↑ Woodworking videos showing how to cut ellipses with a router.

- Charles D.Miller, Margaret L.Lial, David I.Schneider: Fundamentals of College Algebra. 3rd Edition Scott Foresman/Little 1990. ISBN 0-673-38638-4. Page 381

- Coxeter, H. S. M.: Introduction to Geometry, 2nd ed. New York: Wiley, pp. 115-119, 1969.

- Ellipse at the Encyclopedia of Mathematics (Springer)

- Ellipse at Planetmath

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Ellipse" from MathWorld.

External links

Template:Commonscat

- Apollonius' Derivation of the Ellipse at Convergence

- Ellipse & Hyperbola Construction - An interactive sketch showing how to trace the curves of the ellipse and hyperbola. (Requires Java.)

- Ellipse Construction - Another interactive sketch, this time showing a different method of tracing the ellipse. (Requires Java.)

- The Shape and History of The Ellipse in Washington, D.C. by Clark Kimberling

- Collection of animated ellipse demonstrations. Ellipse, axes, semi-axes, area, perimeter, tangent, foci.

- Ellipse as hypotrochoid

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}C&=2\pi a\left[1-{\dbinom {.5}{1}}^{2}{\dfrac {\sin ^{2}(o\!\epsilon )}{1}}-{\dbinom {1.5}{2}}^{2}{\dfrac {\sin ^{4}(o\!\epsilon )}{3}}-{\dbinom {2.5}{3}}^{2}{\dfrac {\sin ^{6}(o\!\epsilon )}{5}}\cdots \right]\\\\&=2\pi a{\Big [}1-{\frac {1}{4}}\sin ^{2}(o\!\epsilon )-{\frac {3}{64}}\sin ^{4}(o\!\epsilon )-{\frac {5}{256}}\sin ^{6}(o\!\epsilon )\cdots {\Big ]}\\\\&=2\pi a\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }\left\{-\left[\prod _{m=1}^{n}\left({\frac {2m-1}{2m}}\right)\right]^{2}{\frac {\sin ^{2n}(o\!\epsilon )}{2n-1}}\right\}\end{aligned}}}](https://services.fandom.com/mathoid-facade/v1/media/math/render/svg/95d8da63dfcf7f523c14baca4783615750c64285)

![{\displaystyle C\approx \pi \left[3(a+b)-{\sqrt {(3a+b)(a+3b)}}\right]}](https://services.fandom.com/mathoid-facade/v1/media/math/render/svg/148fb930deeb7d07f0f776091546a23871e4ae2b)